Rational Diffusion

(“Scrappy Chair Design Challenge” submission)

The SFMoMA hosted an exhibition of contemporary furniture for the better part of a year over 2022 and 2023. To commemorate the close of this exhibition, the museum organized a public-facing furniture design challenge and invited designers to create chairs from leftover materials from other installations. I was in a bit of a creative rut at the time, and my partner suggested this challenge as a good sprint project.

The museum’s design challenge provided dimensional lumber and plywood as the starting set of materials, and the final chair needed to be at least 75% made of the supplied materials. I decided that I’d voluntarily further constrain myself to only use the provided materials (besides screws and glue). This seemed like a good way to fully commit to the ethos of reuse offered by the challenge.

I started by spending hours combing through Pinterest for visual inspiration. I’ve found that since Pinterest presents images adjacent to other visually similar concepts, it’s a great tool for quickly honing my opinion of design themes in the context of a larger landscape. I wanted to showcase the basic materiality of the raw materials provided. The collection of design inspiration I amassed showcases this intent.

I also spent good time browsing through The Atlas of Furniture Design, an incredible book I was gifted last year. I feel like I’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of the wealth of inspiration collected in this book. I’m looking forward to spending more time refreshing my understanding of design concepts and history by reading it carefully in the years to come.

A subset of the design inspiration I collected.

A wide range of the chairs I generated through DALL·E 2.

I sat and sketched a wide range of concepts. Very few of my initial directions stoked any creative energy in my gut. I had spent enough time collecting inspiration to know that what I was generating wasn’t interesting, but I was unsure of how to rapidly broaden my generative range before a fast approaching deadline.

Like much of the internet-enabled public, I’ve been quite intrigued by the rapidly increasing accessibility of generative AI tools. I’ve dabbled in using them in a pretty specific way. Rather than trying to create otherworldly or implausible yet believable photorealistic images, I’ve been curious about integrating generative AI tools into a my development workflow for industrial design concept work. I like to think that I have been steadily improving my ability to articulate and defend my design vision over my career, but my rapid sketching and visual concepting skills unfortunately haven’t grown at the same rate. Generative AI has been a novel and welcome tool for me to add to my prototyping toolbox. Using a tool like DALL·E 2 is a fantastic counterpoint to the speed of browsing inspiration on a platform like Pinterest. In a sense, it’s two more prisms in the chain: I have an opportunity to distill the wide range of content I’ve consumed into tailored prompts that I can then expand through the AI tool.

On the left, I’ve gathered dozens of the concepts I curated and evaluated. I’ve presented my top candidates in the carousel above and my favorite concept in the image below.

At first, I wondered if I had wasted my time by sketching and researching content before turning to this tool, but I quickly realized that the earlier research was a very good way to rapidly immerse myself in the topic and consume loads of content. Even though I hadn't originally planned on leveraging AI for this project, my early research ended up being a useful method to "prime" my eyes and brain to understand the generated work in the context of reality.

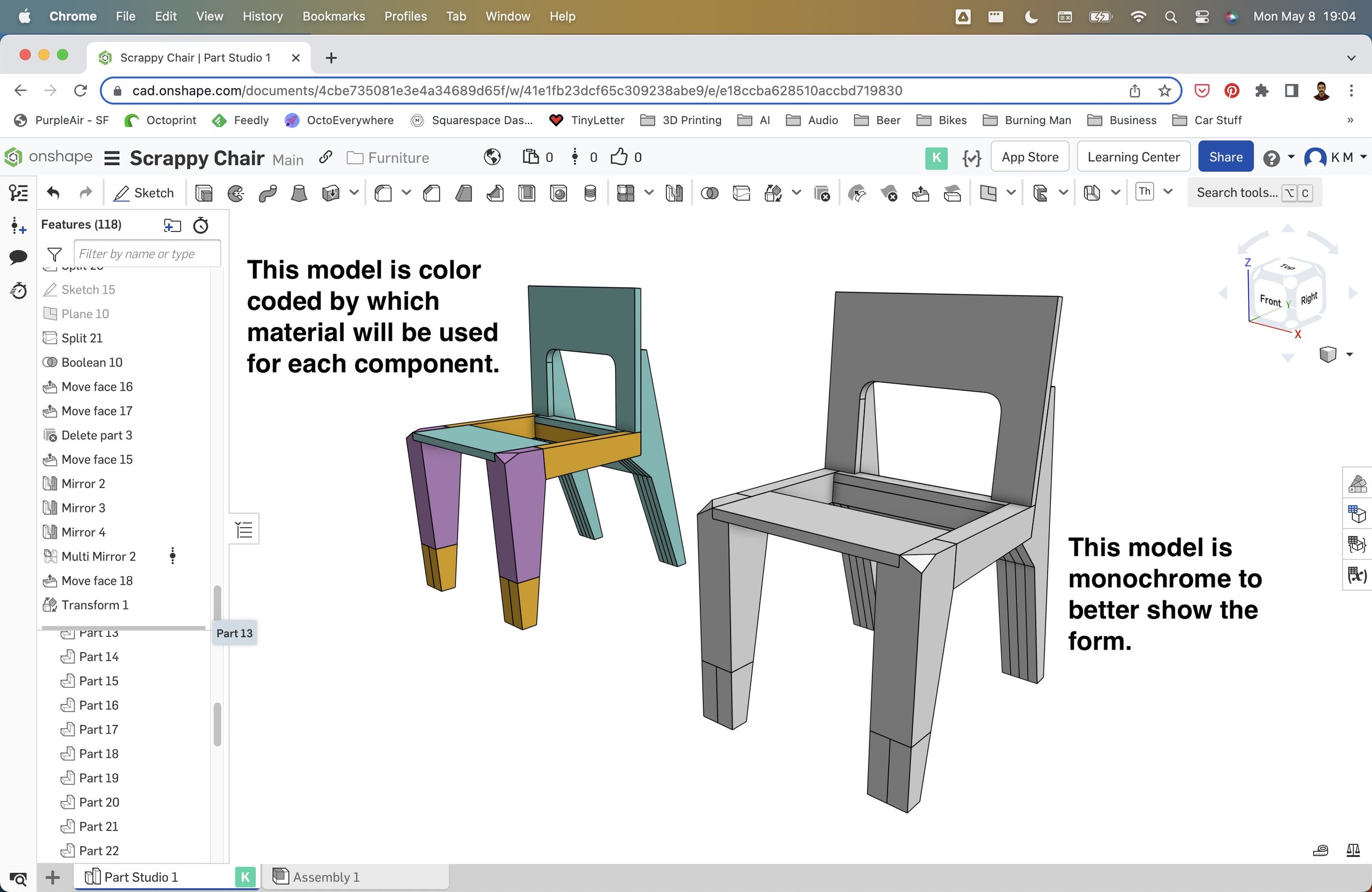

My work didn’t end with by selecting a compelling AI rendering. I’m still understanding the the interplay of generative AI tools and design. In this project, I felt like I had multiple roles: first as a curator to guide the prompts and results, but then as a translator or interpreter to turn the AI model into reality. I started this translation by creating a realistically dimensioned model that visually resembled the rendering. I referenced a guide to "ideal" chair dimensions to determine certain details such as the seat angle, back angle, and core dimensions. I created this model as a single body without understanding how I was going to make it from the provided materials, just to get a dimensionally correct monolith into three dimensional space. I 3D printed several scale models of the form in order to better understand it in the physical world.

As I was creating this first interpretation, I realized that while the AI model was aesthetically compelling, there was a fundamental problem with the utility of the suggested chair. The AI model had a giant cutout right where you would normally be resting your posterior. I considered deleting this cutout in service of making the chair functional, but I ultimately decided to stay true to the AI model. I think it makes the piece more interesting and honors the tool that I used to generate the concept. The generative model is trained on images, not principles, and the visually interesting seat cutout that renders the chair "useless" is a perfect example of this tension.

In the DALL·E 2 rendering, there are some strong visual elements that held my attention. The sides of the seat appear to be solid wood that is contiguous with the front legs. I think this is one of the most successful details of the digital generation. This would be impossible to achieve literally given the dimensions of the provided lumber - a constraint that was hard to provide specifically as an input to the generative tool. I saw this as an invitation to further interpret the AI model. I prioritized a clean solid wood face when viewed from the front instead of from the top. This decision is itself a reflection of the true process - how am I, the designer/translator/curator, making myself known in the end result?

Even though DALL·E 2 is able to generate images that imply a three-dimensional body, you are only able to interact with the suggested object through a two-dimensional image. If a detail is out of view in the image, it's impossible to be honest to the model when you're creating a three-dimensional interpretation. I thought about this when modeling the large angled face between the back legs and the underside of the seat. Unlike with the feet, which are clearly implied through the visible image, this angled face is part of a completely uncreated structure. I resolved this unknown detail by applying constraints of my own. I decided to create a bounded volume with sheet plywood in a nod to the fact that this part of the model was "unknowable" through my limited perspective. I consider the sheet plywood to be representative of a low-res polygon surface model, which I in turn interpret as the lowest level three-dimensional model. This, in turn, is a way to suggest that I am "filling in the blank" as quickly as possible for this feature. This was the last detail I needed to pin down in order to finalize translating the rendering into a model I could build with the provided materials. I’ve included a color-coded screenshot below to clearly identify where different materials would be used when building the chair.

I hadn't considered the name of this chair until opening the submission form. True to form, I utilized ChatGPT to help generate names. The chatbot kept suggesting "Fusion" as an element in the name, and it took me a while to realize that this was in reference to the "diffusion model" architecture of DALL·E 2. I also wanted to honor the themes of design I brought forward with this model - and that's how I ended up with the final name - “Rational Diffusion”.

In the end, my chair wasn’t selected as a finalist. I’d of course love an opportunity to bring this model into the real world, but I still see the time I spent on this challenge as tremendously valuable. I’m happy with how much I continued to refine my perspective on emerging design tools, and I’m excited to keep stoking this creative energy as I move forward.

Note: much of the above text is taken from the artist statement I submitted as part of the challenge. The full text is available here if you’d like to read the original submission.